By Alvin Finkel

Interviews Relating to Systemic Racism in Alberta

Systemic racism has a long history in Alberta that dates back almost to the arrival of Europeans in this territory. The first Europeans were fur traders. They required Indigenous people to serve as the work force that trapped animals and prepared furs for market, guides throughout the territory, and transporters of furs to the Great Lakes and Hudson Bay. Unlike plantation labour, the fur trade ruled out unfree labour.

A Buffalo Rift, by Alfred Jacob Miller, 1867. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, C-000403.

But within the fur-trading companies, no one whose blood was not fully European could rise above menial labour positions. And as the fur trade ceded to agricultural settlement, Indigenous people were viewed as obstacles to the “white man’s progress.” Treaties that hemmed Indigenous people in on small reserves were imposed. The Department of Indian Affairs set 10 acres as the size of an Indigenous farm while Euro-Canadian homesteaders received 160 acres of generally more fertile land. The system regarded First Nations as potential subsistence peasants and Euro-Canadians as commercial farmers. Metis were ignored altogether and given no land. Forced to establish shacks along “road allowances” and move when those were developed, they were threatened with extermination by tuberculosis and malnutrition in the 1930s. The Alberta government then established modest Metis settlements.

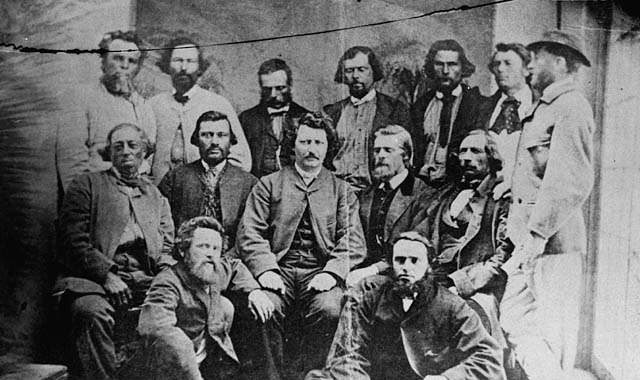

Councillors of the Provisional Government of the Métis Nation, 1870. Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada, a012854.

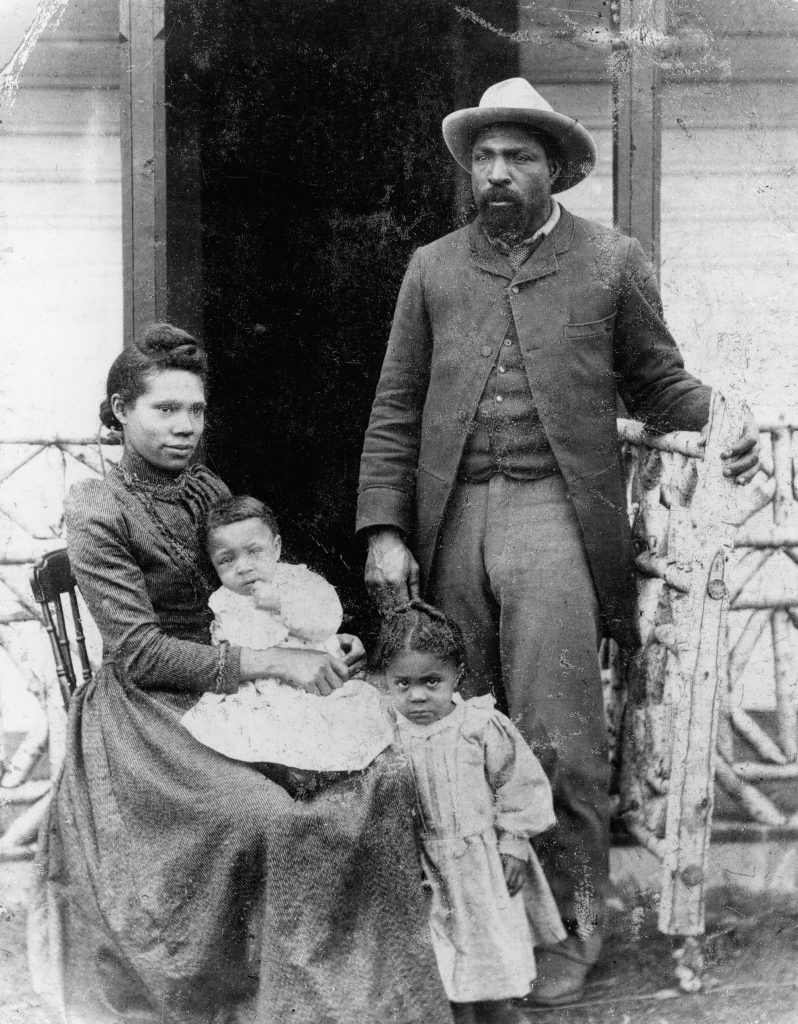

In the pioneer colonial years of Alberta, there was a clear ethnic hierarchy in the work force. Skilled labour jobs were reserved for Anglo-Saxons, while central, eastern, and southern Europeans worked jobs labelled unskilled, including the dangerous jobs in coal mines. Immigration policy discriminated against non-whites. But Chinese labourers were imported to do the most dangerous jobs in building the CPR and 1500 of them died. Afterwards, they were restricted to jobs in laundries and as servants. A steep head tax on Chinese immigrants made it impossible for most of them to bring their families to Alberta from China. African-Canadians could find few jobs other than railway porter. When African-Americans began arriving in Alberta to establish agricultural communities, the provincial and federal authorities quickly clamped down on further migrations. Indigenous workers were mostly restricted to farm labour and handyman jobs when they were allowed to leave their reserves at all.

John, Nettie, Mildred and Robert Ware, Black rancher and family, Southern Alberta, [ca. 1896], [NA-263-1], Courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary.

Barriers to non-white immigration remained strict until the 1960s when labour shortages could no longer be accommodated by Western European immigration since that region had become as wealthy as Canada and its residents no longer saw much reason to migrate to North America. There had been a small migration of Caribbean workers as domestic workers in the 1950s and there was a similar feminine focus in the 1960s recruitment of Filipino nurses.

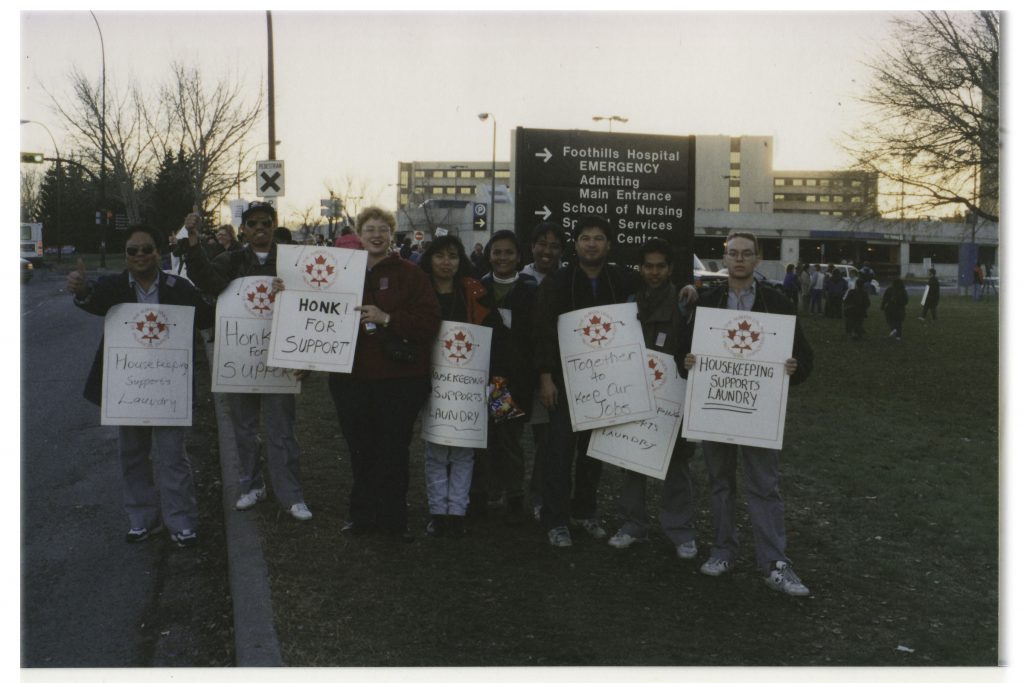

Many recent immigrants to Canada from countries such as the Philippines work in Alberta’s service sector in low- wage jobs despite the fact that many are qualified to work in professional occupations such as nursing. Photo courtesy of G. Christie.

As immigration from outside Europe increased, so did discrimination in employment and housing and much more. Human rights groups formed and pressured the government to pass the Human Rights Act of 1966 which prohibited racial discrimination. The Alberta Human Rights Branch was established to enforce the legislation. Subtle forms of discrimination in both employment and housing nonetheless continued; hundreds of years of colonialist stereotypes and racist practices would not evaporate overnight.

Legislated racism also continued in many forms. Immigrants were mostly professionals but those from non-white countries repeatedly found their educational and professional qualifications rejected as they sought work. While some successfully fought to gain entry to their professions, many more worked in poorly paid unskilled labour jobs and put their hopes in their children getting a Western education and being accepted.

Photo courtesy of Migrante Alberta.

The growing army of temporary foreign workers, whose numbers reached 77,000 in the early 2000s, could harbour no such hopes. Brought into the country to do menial labour on farms and in many urban and industrial settings, they were tied to a single employer and had few rights and no path to citizenship.

Temporary, landed, or permanent, non-whites were treated by the justice system as suspicious characters no matter how they conducted themselves. Blacks, having been enslaved by Europeans, and Indigenous people, having been dispossessed, were treated particularly harshly, with some Europeans, perhaps sub-consciously, trying to validate their ancestors who had treated these peoples with so much inhumanity. The policing and court systems were particularly oppressive, profiling, arresting, and imprisoning Indigenous peoples and African-Canadians in numbers extremely disproportionate to their weight in the population.

Throughout, Indigenous peoples, African-Canadians, Asian-Canadians, and Latinos have fought oppression while contributing to the development of Alberta through their labour, their cultural contributions, and their political involvement.

Interviews Relating to Systemic Racism in Alberta

Read Black Lives STILL Matter by Donna Coombs-Montrose.

Read We Want to Breathe by Donna Coombs-Montrose

Read about a shocking white supremacist event in Alberta in 1990, denounced by a human rights Board of Inquiry.

Read about some reports of cases involving racial discrimination.

See also: Black Communities in Alberta; Indigenous Labour History Project; Temporary Foreign Workers