by Alvin Finkel

Interviews relating to Coal Mining in Alberta

INTRODUCTION

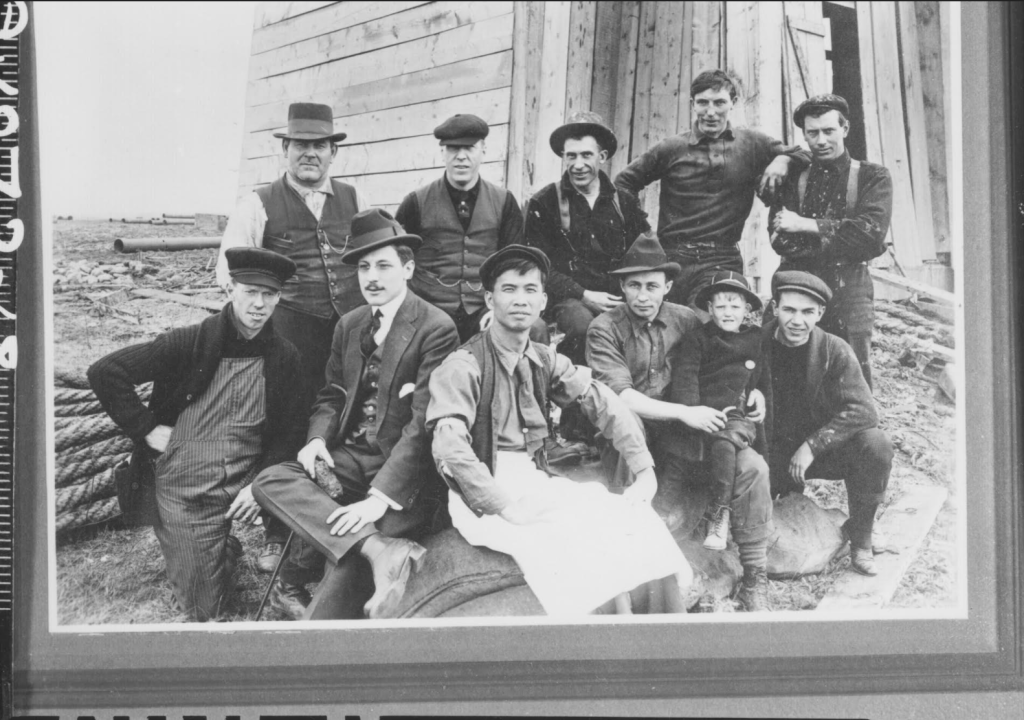

As agricultural and then urban settlers poured into Alberta from the 1880s onwards, they depended on coal miners to provide them with the fuel that heated their homes. The trains that moved raw materials out of the province and manufactured products into Alberta were also dependent on the miners. By 1920 the CPR, which owned a number of the coal mines, purchased 90 percent of Alberta’s bituminous coal. Mines were spread across the province with the largest concentration to be found in the Crowsnest Pass region.

The mining companies tried to make profits by paying the miners poorly and skimping on occupational health and safety measures. Many miners responded by joining unions, particularly the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) District 18 which had formed in 1890. Mine explosions were common and led to many deaths, particularly in the Crowsnest Pass. In 1902, 128 men died in a mine explosion in Coal Creek Pass, where another 34 would die in an explosion in 1917. In 1903, 90 men died in the Frank Slide on Turtle Mountain and 30 died in an explosion in Bellevue in 1910. The worst mining disaster in Canada’s history was an explosion on June 19, 1914 at the Hillcrest Coal and Coke Company mine on the Alberta side of the Crowsnest Pass: 189 miners died that day. Experts hired by District 18 determined that the company had ignored Mines Act requirements to provide fresh air to every mine seam, which would have neutralized the noxious gas that provoked the explosion. A coroner’s inquest jury confirmed that analysis. But the company faced no criminal charges.

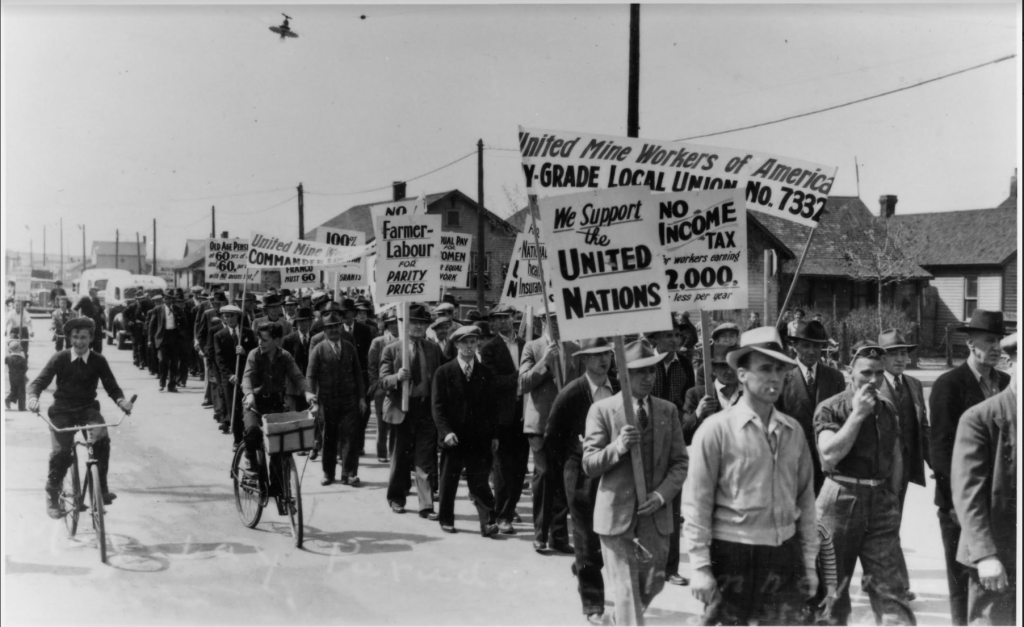

The ruthlessness of the mining companies and the indifference of the Alberta government—they passed mine safety legislation but failed to enforce it—caused the unionized miners to strike frequently. Miners became the largest base for union radicalism and socialist politics in Alberta for decades. Crowsnest Pass miners elected Socialist miner Charles O’Brien to the legislature in 1909, giving the province its first socialist MLA. It was miners who led the effort to create the Alberta Federation of Labour in 1912, whose votes gave the overwhelming majority of Alberta unionists’ endorsements to the radical One Big Union (OBU) movement in 1919, and whose militancy during the Great Depression inspired workers and the unemployed generally to demand state interventions to provide work or adequate welfare for all Albertans. Alberta miners had lost their confidence in the UMW because the American leadership of the union seemed to be increasingly in the pockets of the mining companies. The Alberta miners’ dues went to the Virginia headquarters of the UMW, but their requests for strike support were increasingly ignored.

In 1919, 96 percent of Alberta miners voted to join the OBU, which called for solidarity strikes of all workers when any set of workers were on strike. Every mine in the province went on strike in May, some calling for an end to the piece work system which impoverished miners and deterred efforts to resist occupational health hazards, and others calling for guarantees of sufficient hours of work each month to allow households to survive. Governments, employers, and the UMW united against the miners. High unemployment guaranteed the availability of scabs, who were protected by private and state police to keep mines open in the Crowsnest Pass until the striking miners were starved into submission. In Drumheller, British-origin returning soldiers beat up striking central European-origin workers and dragged them back to the mines. The federal government ordered all OBU members to rejoin the UMW or lose their jobs forever.

The forced return to the UMW after World War I did not end the bitterness among miners with their local’s subservience to the American leadership. OBU miners’ leader P.M. Christophers was elected as Labour MLA for the Crowsnest in 1921, a demonstration of the continued support of the miners for the OBU despite an undemocratic coalition of forces having forced them to abandon that union. In 1922, Slim Evans, UMW secretary in Drumheller, used union dues meant to be sent to the international to feed starving miners on strike. The American leadership charged him with “fraudulent conversion,” and he spent three years in jail. In 1925, a secession movement among Alberta miners produced the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada, which was largely Communist-led. The UMW and the MWUC battled for allegiance of the miners until 1935 when the two groups united under the UMW banner.

Interviewees from miners’ families recall the union struggles from the 1930s against layoffs and wage reductions and the struggles during and after World War II for better ventilation in mines, decent wash houses, and guaranteed pensions. They relate the solidarity within mining communities and the many entertainments that miners and their wives organized to make life bearable in communities where coal dust was everywhere and most people lived in shacks without running water and indoor toilets. Miners’ wives hauled water over long distances, canned, made their own bread, wine, and clothing, and crocheted and planted to provide colour to otherwise drab, unfurnished homes. While community solidarity guaranteed that a family without income would be helped to survive, patriarchal norms ensured that no one interfered when a miner or other male community member beat his wife or children.

Alberta’s coal mines worked overtime during World War II to meet demand. But by the late 1940s, demand for coal declined as the CPR and CNR switched from coal to diesel fuel. Coal production declined from 9 million tons in 1946 to 2 million in 1961. Miners were forced to move out of their communities, often with virtually no transitional assistance from either mining companies or governments. For those who remained at work, the chances of death or severe injury on the job remained great. Limited compensation to miners’ families when the miner died or was maimed forced wives and widows to seek whatever poorly paid “women’s work” was available to help to feed their families.

In the 1960s coal-fired power generation revived coal mining to a certain degree. But coal mining never regained its earlier pride of place as an employment sector in Alberta and in recent years, the negative impact of coal on climate change has made the future of this industry debatable. The threat of selenium leaking into major waterways and making the water unusable as well as a desire to protect the Rocky Mountains for tourism and recreation led to a ban on developing new coal mines on the eastern slopes of the Rockies in 1976. A United Conservative Party government in 2020 repealed that ban thanks to lobbying by Australian billionaire coal companies. That produced a backlash that seemed to unite most Albertans but especially ranchers, farmers, and Indigenous people whose livelihoods were most at threat from the consequences of any new mines in the region.

Our interviewees collectively provide a nuanced history of coal mining in Alberta: solidarity against rapacious employers and community efforts to help those in need, on the one hand, but racism and sexism within the coal miners’ communities, on the other; gains from hard-fought strikes, on the one hand, and losses resulting from corporate and state decisions to move away from coal use, on the other. All told though, the voices in these interviews speak to complex and lively communities, some of which have disappeared and others which have either maintained their connection with coal or survived by transitioning to other industries.

Though coal mining may have been mostly relegated to Alberta’s past, the legacy of those hard-working miners lives on in radical trade union and political traditions which they were the first to spearhead in the province.

Interviews relating to Coal Mining in Alberta – See list at bottom of page

Additional Resources

Baker, William M. “The Miners and the Mounties: The Royal Northwest Mounted Police and the 1906 Lethbridge Strike.” Labour/Le Travail 27 (Spring 1991): 55-96.

Buckley, Karen. Danger, Death and Disaster in the Crowsnest Pass Mines, 1902-1928. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2004.

Chambers, Allan. Spirit of the Crowsnest: The Story of Unions in the Coal Towns of the Crowsnest Pass. (Download PDF) Edmonton: ALHI and the Alberta Federation of Labour, 2012.

Jacobson, Kate. “Remembering the 1919 Drumheller Strike.” Briarpatch, 30 April, 2018.

Langford, Tom and Chris Frazer, “The Cold War and Working-Class Politics in the Coal Mining Communities of the Crowsnest Pass, 1945-1958,” Labour/Le Travail 49 (Spring 2002): 43-81.

Norton, Wayne and Tom Langford. A World Apart: The Crowsnest Communities of Alberta and British Columbia. Kamloops: Plateau Press.

Ramsey, Bruce. The Noble Cause: TheStory of the United Mine Workers of America in Western Canada. Calgary: UMWA District 18, 1990.

Seager, Allen. “Class, Ethnicity, and Politics in the Alberta Coalfields, 1905-45,” in Dirk Hoerder, ed., “Struggle a Hard Battle”: Essays on Working Class Immigrants (Dekalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois Press, 1986): 304-324.

Seager, Allen. “”The Pass Strike of 1932.” Alberta History 25,1 (1977): 1-11.

Seager, Allen. “Socialists and Workers: Western Canadian Coal Miners, 1900-1921.” Labour/Le Travail 16 (Fall 1985): 23-59.

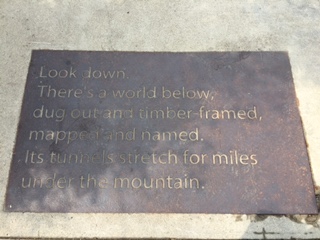

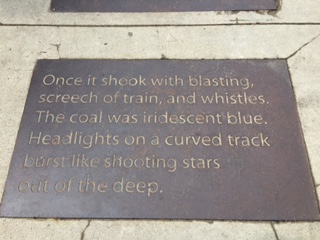

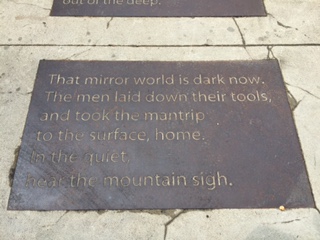

Once a mining town, Canmore is now a super-gentrified mountain resort town. But it has memorialized its mining past, as the three images here suggest. Photos courtesy Jo-Ann Kolmes.

Interviews Relating to Coal Mining in Alberta

Joyce Avramenko describes the roles of coal miners’ wives in their communities and the extent of domestic abuse that many of these women experienced.

Crowsnest Pass Group 1: The 13 people interviewed together in Coleman comment on wide-ranging issues dealing with work and daily life in the Crowsnest Pass.

Crowsnest Pass Group 2: The 9 people interviewed together in Coleman comment on wide-ranging issues dealing with work and daily life in the Crowsnest Pass.

Drumheller Group: The 4 people interviewed together in Drumheller in 2003 discuss work and living conditions in the Valley and efforts to counter exploitation of miners and their families.

Leon Dyrgas and Bill Pasemko were long-time miners in Canmore-area mines who were interviewed together. When the mines closed, they received no severance pay and Dyrgas received no pension while Pasemko received a pittance of a pension.

Bruno Gentil spent fifty years working for the mines in Coleman as first a horse trainer and driver, then later as a blacksmith.

Tilly Herman, a miner’s daughter in East Coulee, and a miner’s wife in Drumheller, recalls the lives of miners’ children and wives, both in terms of hardships and community entertainments.

Kate Jacobson is an internal organizer for the Alberta Union of Provincial Employees (AUPE). She has also worked in various non-union jobs and has years of experience as a social and environmental militant and as an historical analyst of such struggles as that of the Drumheller miners after World War I to form a One Big Union affiliate.

Cathy Jones was a long-time registered nurse in both Toronto and Banff when she became involved in heritage work in Canmore that included museum displays of the lives of miners, miners’ wives, and miners’ families.

Mary-Beth Laviolette is a curator, author, and former CBC journalist whose research and writing have included projects involving a number of Alberta coalmining communities.

Roy Lazzarotto mined in the Crowsnest Pass from 1950 onwards and fought successfully through his union to improve mine safety.

Liz and Steve Liska describe the many dangers of working underground as well as the day-to-day experience of work and life raising a family in Coleman and Bellevue.

John Mitchell grew up in the coal-mining town of Luscar and became a coal miner like his father until the Coal Branch mines were all closed down.

Clara Montgomery, who grew up on a farm in the Drumheller area, describes the coal-related work of members of farm families.

Lena Shellian, born and raised in Canmore, was the daughter, grand-daughter and wife of coal mine workers, and watched her dad and her husband die of silicosis.

Jack and Jan Tarasoff (see also Jan Tarasoff) were long-time activists in the Communist Party in Calgary and in the politico-cultural activities of the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians.