Interviews Relating to Occupational Health and Safety in Alberta

THE INJURIES OF CLASS: ADDICTIONS, MENTAL HEALTH, AND THE WORK WORLD

INTRODUCTION

by ALVIN FINKEL

“In 2003, six hundred and thirty thousand Canadian adults were injured on the job severely enough to limit their activity. Approximately 300,000 of these injured workers required time off to recover.” (Bob Barnetson, The Political Economy of Workplace Injury in Canada (Athabasca University Press, 2010)

Limited legislation was passed to protect workers in what is now the Province of Alberta in the years before Alberta became a province in 1905. From 1870 to 1905 the settler regions of the Prairies west of Manitoba were organized as the North-West Territories. An employee or their family could sue a company for negligence after an “accident,” but that required finances that most aggrieved individuals and families did not have. Accident is in quotes here because, when an employer makes money by making people work at speeds that make caution difficult or when they fail to provide adequate job orientation or when they fail to take safety measures because it is cheaper to avoid them, “accidents” are events waiting to happen. The word “accident” implies that something is not predictable and no one is to blame. But many so-called accidents should be viewed as something closer to manslaughter by employers. So, here, we will be using the word “incident” to replace “accident.”

There was no workers’ compensation for injured workers or state or employer compensation for families of a worker who died on the job. The one significant exception was the Coal Mines Regulation Ordinance of 1893. It provided safety regulations for ventilation in mines, but no provisions were made for its enforcement.

In 1906, the first Alberta provincial government passed the Coal Mines Act, which created a mines branch to regulate the industry, including ordering mining companies to implement particular safety provisions. But only two people were employed to inspect mines and ensure that safety legislation was complied with. In practice there were few penalties for companies and their owners and managers who failed to comply with the safety rules.

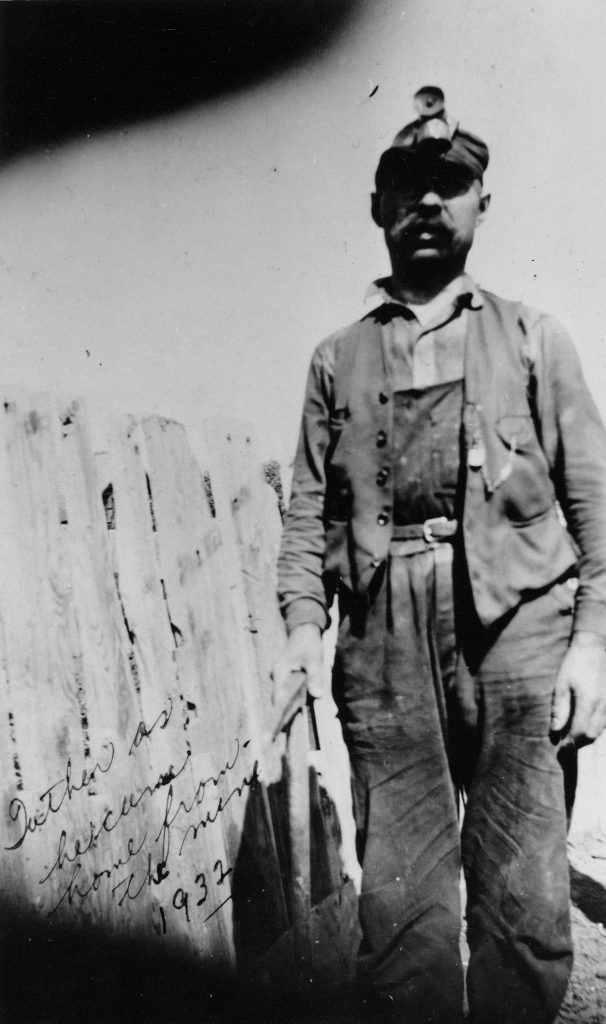

Coal mining was a dangerous industry made even more unsafe when owners ignored safety considerations. Miners were constantly victims of broken backs and bones. Over time most would develop black lung disease from inhaling coal dust. Initially they experienced shortness of breath and coughing. Eventually their lungs turned black and they died slow, painful deaths from their destroyed respiratory system.

While coal dust was a slow killer, mine explosions meant instant, mass deaths. They were frequent in Alberta and some had particularly large death tolls, including Coal Creek Pass in 1902 with 102 deaths, Bellevue in 1910 with 30 deaths, Hillcrest in 1914 with 189 deaths, and Nordegg in 1941 with 29 deaths. The Frank Slide of 1903, with 90 deaths, was another deadly event. Hillcrest was the worst, with 189 deaths at the Hillcrest Coal and Coke Company mine in the Alberta section of the Crowsnest Pass. Charles Plummer Hill, the owner, had resisted the province’s efforts on behalf of mine safety as an intrusion into his private affairs. He ignored the province’s rule that safety lamps be issued to all miners, a requirement implemented after an explosion severely burned two miners in 1908. The jury at the coroner’s inquest for the 1914 explosion concluded that Hill had violated the Mines Act requirement to provide fresh air to each mine seam to render harmless noxious gases that can cause explosions. But Hill was never called to account for causing the unnecessary deaths of 189 men. An historian of coal mining in Alberta who glorifies the early coal bosses in the province and their disdain for government interference glosses over Hill’s responsibility for these deaths. But, from a worker’s point of view, Hill’s pursuit of profit at the expense of workers’ lives was a criminal psychopath.

Blue-collar jobs generally were unsafe because employers, single-mindedly focused on profits, paid little attention to orientation of new workers, maintenance of equipment, or hiring enough workers to make safety practices possible. They might tell workers to be careful on the job, but then made a mockery of such advice with constant speed-ups to improve productivity, with the careful workers losing their jobs or receiving reduced pay for their troubles. Numerous incidents in the packinghouse industry during the 1930s, for example, were attributed to speed-ups.

Until 1918, those who were injured had to seek compensation via the courts. They had to prove that the employer had been negligent. While juries were often sympathetic to arguments from employees or the families of someone who had died in a workplace incident, few workers or their families could afford to sue. Unions pushed for workers’ compensation legislation, which had first been implemented in Germany in the 1880s. It required employers to make monthly contributions to a fund that would provide income to workers injured on the job until they were able to return to work, if ever, or to their families when an injury led to a worker’s death. Such legislation was first implemented in Canada in Quebec in 1909. Alberta’s Workmen’s Compensation Board, established in 1918, like other such boards in Canada at the time, initially limited compensation to blue-collar jobs deemed particularly physically dangerous and only physical injury on the job would qualify a worker for income. As the name of the board suggested, women workers, though many worked in physically dangerous occupations, were rarely eligible for workers’ compensation. The largest category of women’s paid work was domestic labour. But house servants and other domestic workers were excluded from coverage in the WCB legislation. That remains the case today. Also excluded were farm labourers, whose work was particularly dangerous. The political power of farmers and the political weakness of farm labourers has meant that to this very day farm workers are treated more like workers in authoritarian countries than like workers who live in democracies. Their right to safe and healthy work is diminished by claims that “farm culture” takes precedence over the duty of the state to ensure that workers can count on going home alive and in one piece at the end of the day and get compensation when that doesn’t happen.

Workers at Canada Packers taking a union vote after a slowdown strike (a strike where workers show up for work but deliberately slow down its pace to a crawl). Courtesy Provincial Archives of Alberta, BL791.1

Almost from the start attitudes to workers’ compensation reflected social class differences. Employers viewed the legislation as a suitable barrier to employer liability legislation that might punish employers who were responsible for unsafe working conditions. Workers, through their unions, argued that it should not prevent governments from implementing tough safety legislation with severe penalties for defiant employers. Employers insisted that most incidents were caused by negligent workers. Unions argued, in contrast, that most incidents were caused by employer callousness and the placing of profits over workers’ safety. Employers called for workers’ compensation to cover only a small portion of a worker’s income while unions wanted compensation to fully replace the wages of an injured worker and families to receive full replacement of the wages of a worker who died because of a work incident. Employers wanted the Board to force workers back to work as soon as possible after an injury and cut them off their compensation while unions wanted the Board to accept the verdict of doctors as to when a worker should be required to return to work. On the whole, throughout the century and more that workers’ compensation has existed, employers have called the shots. But unions have, over time, managed to get the wages replaced gradually increased from 40 percent to 90 percent.

Unions fought employers for improved safety conditions. Miners’ unions negotiated better orientation of their members, closer examination of mine conditions, and better ventilation. Pulp and paper unions similarly won guarantees for safer conditions in the mills. The Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers, one of the predecessors of today’s Unifor, observing that workers handled chemicals with almost no safety precautions, insisted that management implement a host of measures to protect worker safety. In many jobs, as it became clear that asbestos was a slow killer, demands for its removal became important. But almost everywhere the pace of work imposed by management meant that work tragedies were inevitable.

In the construction industry, workplace safety, though improved over earlier periods, remained quite limited even in the boom years of the 1960s and 1970s. In ALHI’s video, “Waltzing with the Angels,” the Metis ironworkers who did the most dangerous jobs building the skyscrapers of downtown Edmonton describe the self-made harnesses they used as they worked hundreds of feet above the ground. They indicate that they generally provided their own hardhats and used cotton batting as earplugs to stifle the impossible noise as they worked. Many of their fellow ironworkers died because of the lack of safety provisions. (See “Waltzing with the Angels” in ALHI Documentaries.)

These seven men, six of whom are Métis, were ironworkers from the mid-1960s onwards who were responsible for doing the most dangerous jobs building the CN Tower and other business and apartment skyscrapers that dot the downtown and surrounding areas of Edmonton.

The Alberta Federation of Labour and its member unions made the improvement of health and safety legislation and enforcement a priority in the 1960s and 1970s. Inspectors focused more on persuasion than coercion, causing many employers not to fear consequences when they violated health and safety legislation.

In 1973, the Progressive Conservative government of Peter Lougheed, responding to union campaigns, passed the Occupational Health and Safety Act, which gave workers the right to know about occupational health hazards, to participate in joint worker-management Health and Safety committees, and to refuse unsafe work. Union members gained from these protections. But the three quarters of Alberta workers who were not unionized received little protection because the government did little to directly enforce the provisions of the Act. Even the unions often had to respond militantly to management’s unwillingness to accept workers’ rights to refuse unsafe work. In 1980, for example, 26 members of the Canadian Paperworkers Union in Hinton were fired when they refused to work in a snowstorm. The union closed down all the work camps in the woods the next day, causing the company to back down and rehire the fired workers.

In 1989, in an important national case involving three Safeway workers in Manitoba, the Supreme Court ruled that pregnancy must be treated as a health issue, and so all health benefits must be extended by an employer to pregnant employees. The Alberta government did not seem to get the message. When Alberta nurse Susan Parcels informed the Red Deer Auxiliary Hospital that she was about to have her second child and take maternity leave, she was told that she had to prepay all of her benefits. With support from the United Nurses of Alberta, Parcels asked the Alberta Human Rights Commission to rule that her benefits should be automatic as they would be for any other employee on a sick leave. She won the case and in 1992 the Court of Queen’s Bench upheld the Commission ruling when the employer appealed the ruling. (See the ALHI video, “Susan Parcels Case,” in ALHI Documentaries.)

Sometimes it required a strike to force a company to respond to workers’ concerns about the safety and cleanliness of their workplace. The paper mill in Hinton, for example, had asbestos insulation throughout its operations. Workers had been trying to clean the mill free of asbestos since 1980 but the company stalled those efforts. Finally in 1997, the workers of Communications, Energy, and Paperworkers 855 took illegal strike action to shut the plant down and forced the management to finally get rid of the asbestos. [See the ALHI video, “Hinton Asbestos Wildcat” in https://albertalabourhistory.org/videos/alhi-documentaries/]

The Occupational Health and Safety Act was amended in 2002 to increase penalties. But the fines often seemed like chicken feed to big corporations and under the Conservative administrations no individual owner or manager was ever charged with a criminal offence that might lead to jail time for causing or risking death or serious injury to workers. The unions demanded that Health and Safety Committees become compulsory in all workplaces.

The NDP government elected in 2015 set up independent commissions to review both the Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Act and the operations of the Workers’ Compensation Board system. This led to the legislation of sweeping pro-worker changes in 2017. The union-demanded joint workplace health and safety committees would be implemented for all employers with more than 20 workers while employers with 5 to 19 workers would have to meet with a worker-chosen representative regarding OHS matters. Alberta became the last province in Canada to pass such legislation to benefit all workers, including those without unions.

The right to refuse dangerous work was enshrined, with workers to be paid while an investigation occurred regarding the work alleged to be dangerous. All hospitalizations for serious injuries needed to be reported to the Department of Labour as well as “near miss” incidents. Workplace violence and harassment rules were expanded to include threats and coercion with sexual harassment covered as a health and safety issue for the first time.

In 2019, Siobhan Mangal (pictured) was an apprentice in the Operative Plasterers’ and Cement Masons’ International Association, Local 222 and an apprentice with the Heat & Frost Insulators & Allied Workers, Local 110. In her interview with ALHI she provided detailed descriptions of the training and work in rope access and of the importance of health and safety training.

As for WCB, the cap for maximum insurable earnings on income received from WCB was removed. A lump-sum fatality benefit of $90,772 was created for the survivors of workers who died on the job. Coverage for psychological injuries was provided for the first time, with post-traumatic stress disorder, previously dismissed by the WCB as bunkum, mentioned specifically for coverage. A fair practices office and medical panels were to be appointed to help workers navigate the WCB system. Employers were to be mandated to reinstate injured workers with more than 12 months of service. An Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Council was appointed with the mandate of making recommendations to the minister for improving worker health and safety in Alberta. Perhaps, most controversially, the NDP had earlier bucked the power of agribusiness within farm communities to require WCB coverage for farm labourers.

The NDP’s legislation reflected a growing understanding in the union movement that health and safety on the job refers not simply to protection from physical hazards posed by nature and machines but also to protection from the physical and mental health hazards that humans can pose to other humans. In many jobs in the health sector and in human services, clients/patients can often pose a threat to workers. The need to have specialized workers able to deal with individuals who, for whatever reason, pose physical threats to workers, and to have sufficient staff available to protect individual workers when a confrontation occurs is a health and safety issue that both union contracts and government legislation need to address. Across all jobs, physical, sexual, and mental harassment of workers, particularly women and racialized workers, is also now recognized as a health and safety issue as opposed to simply a “personnel issue.” In our interviews, women workers in the health sector, in particular, discuss challenges to their personal health and safety that at one time would have been seen as outside the realm of occupational health and safety. The issue of overwork and speed-ups, both of which create physical and mental health dangers, are mentioned repeatedly. Having to deal with toxic chemicals without proper training is also often mentioned. Finally, being forced to work alone at night in otherwise empty buildings creates a dangerous work environment for cleaners and other night workers. Long-term care workers sometimes find themselves threatened by residents and many complain of poor training and lack of protective equipment in terms of handling cytotoxic drugs, drugs that require handling with care because of the dangers to someone administering them of becoming very ill through skin contact or inhalation of the drugs.

Many unions provided their own safety training to members. The United Association of Plumbers and Pipefitters Local Union 488 training of new Indigenous members is pictured here. Courtesy Local 488.

The UCP government, elected in 2019, which had the back of employers rather than workers, got rid of much of the NDP OHS and WCB legislation. They shut down the independent Fair Practices Office and the Medical Panels Office. They restored the cap on insurable earnings and they removed the requirement for employers to reinstate workers with over 12 months of service. Under the guise of “cutting red tape” the powers of Joint Health and Safety Committees were significantly reduced and employers received the right to name the worker representatives. While unions were strong enough to prevent that actually occurring on union sites, non-union workers would not be able to fight such a pro-employer provision. The broader “dangerous conditions” which provided the right to refusal for unsafe work was replaced with the weaker requirement that workers could refuse only work that presented hazards that were not normal for a particular kind of work. Near misses would not have to be reported. “Physical, psychological and social well-being” were removed from the health and safety definition. Independent contractors were defined as employers rather than workers, reducing the liability of the ultimate employer to the contractors’ workers. The Occupational Health and Safety Advisory Council was abolished. WCB coverage for farm operations would occur only if the employer wanted it though larger-scale operations would have to provide some form of workers’ compensation coverage. In short, Alberta workers were returned to the Dark Ages when employers’ interests prevailed over the rights of workers to healthy, safe workplaces.

During the COVID pandemic that began in 2020, the continued lack of government and corporate concerns for worker safety was blatantly evident. The meatpacking industry, where corporate concentration has resulted in assembly-line conditions marked by workers being dangerously close to one another and working at inhuman speeds, was most deadly. The largely visible minority workforce at Cargill in High River worked without being provided protective masks in the period before there were any vaccines available for COVID. Over 900 of the roughly 2000 workers contacted COVID. Two of the workers and the father of a third died from COVID in May, 2020. In early 2021, three Olymel workers in Red Deer also died from COVID. Long-term care workers, poorly paid, poorly trained, and overworked because of understaffing, also were infected in large numbers.

Unions of hospital workers were generally more successful in demands for personal protective equipment for their workers. But understaffing, already a health hazard for these workers before the pandemic, created a crisis during the pandemic. Opponents of vaccines often demonstrated at the hospitals and uttered threats to hospital workers, sometimes followed with physical attacks. Some patients who had developed COVID but embraced conspiracy theories threatened workers and sometimes attacked them physically as well as verbally.

Health care unions pressured the Alberta government to provide their members, such as the United Nurses of Alberta member pictured here, with quality personal protective equipment. Courtesy Health Sciences Association of Alberta.

The pandemic also cast a spotlight on the slave conditions under which temporary foreign workers and undocumented workers, whom it is estimated between them account for 1.7 million people in Canada, operate and the impacts on their health and safety. (See our theme essay, interviews, and videos at https://albertalabourhistory.org/temporary-foreign-workers/)

We now know that “occupational health and safety” cannot be separated out from the overall way in which workplaces are organized and who has the power to make decisions about the organization of work. Issues of adequate staffing, adequate consultation of workers by management in respectful ways, adequate staff training, and adequate spending on the safest equipment and protective devices are all inter-related. They all depend on workers having real power in their workplaces. In turn, those rely on having strong labour movements and progressive labour legislation.

Interviews Relating to Occupational Health and Safety in Alberta

Additional Resources

Babcock, Robert H., “Blood on the Factory Floor: The Workers’ Compensation Movement in Canada and the United States,” in Raymond B. Blake and Jeff Keshen, eds. Social Welfare Policy in Canada:Historical Readings.Toronto: Copp Clark, 1995.

Barnetson, Bob. The Political Economy of Workplace Injury in Canada. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2010.

Buckley, Karen. Danger, Death and Disaster in the Crowsnest Pass Mines, 1902-1928. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2004.

Dembe, Allard E. Occupation and Disease: How Social Factors Affect the Conception of Work-Related Diseases. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

Foster, Jason, and Bob Barnetson. Health and Safety in Canadian Workplaces. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2016.

Karasek, R. and T. Theorell. Healthy Work: Stress, Productivity, and the Reconstruction of Working Life. New York: Basic Books,1992.

Lewchuk, Wayne et al. Working Without Commitments: The Health Effects of Precarious Employment. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2011.

Tucker, Eric. Administering Danger in the Workplace: The Law and Politics in Occupational Health and Safety Legislation in Ontario, 1850-1914.Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1990.

Tucker, Eric, ed. Working Disasters: The Politics of Recognition and Response.Amityville: Baywood, 2016.

Witt, John Fabian. The Accidental Republic: Crippled Workingmen, Destitute Widows, and the Remaking of American Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004.