The Alberta Labour History Institute collects, preserves, and disseminates the stories of Alberta’s working people and their organizations. This website includes full transcripts, podcasts, and profiles of our interviewees. It also includes videos, booklets, themed essays, annual calendars, and a link to a book created by ALHI. To learn more about us, visit About.

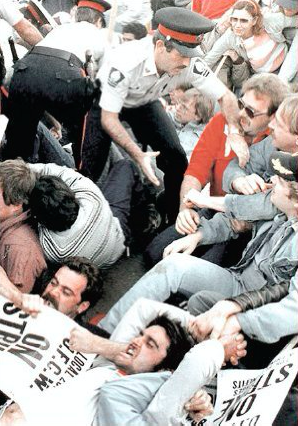

SUMMER OF ’86 in Alberta

SUMMER OF ’86: A THIRTY-YEAR COMMEMORATION, 2016

Interviews relating to the Summer of ’86 in Alberta

Summer of ’86 Video & “Packingtown”

Download the Edmonton event poster

Download the Calgary event poster

The Alberta Labour History Institute (ALHI), with supporting organizations, commemorated the “Summer of ‘86” with three free-of-charge Alberta workshops, a video, and a booklet. Our goals were to commemorate the workers’ struggles of that summer of strikes and solidarity and use them as a basis for discussion of how workers today can confront another outbreak of recession and employers’ attempts to make workers, the victims of the economic crisis, pay for other people’s greed and lack of foresight. That’s what happened in the 1980s. Following a period of uncontrolled capitalist speculative greed, the global economy went into a deep recession in 1982. Employers, private and public, expected workers to make sacrifices so that investors would think that they could make a killing if they started reinvesting. Workers did sacrifice and then were asked to sacrifice more and more to bring about an elusive economic recovery that never seemed to arrive.