Dr. Jennifer Kelly

Interviews with people from Black communities in Alberta

Black communities in Alberta include three main groups: early 20th century American pioneers; immigrants from the Caribbean who began arriving in the 1950s; and African-born immigrants who began arriving in the 1990s.

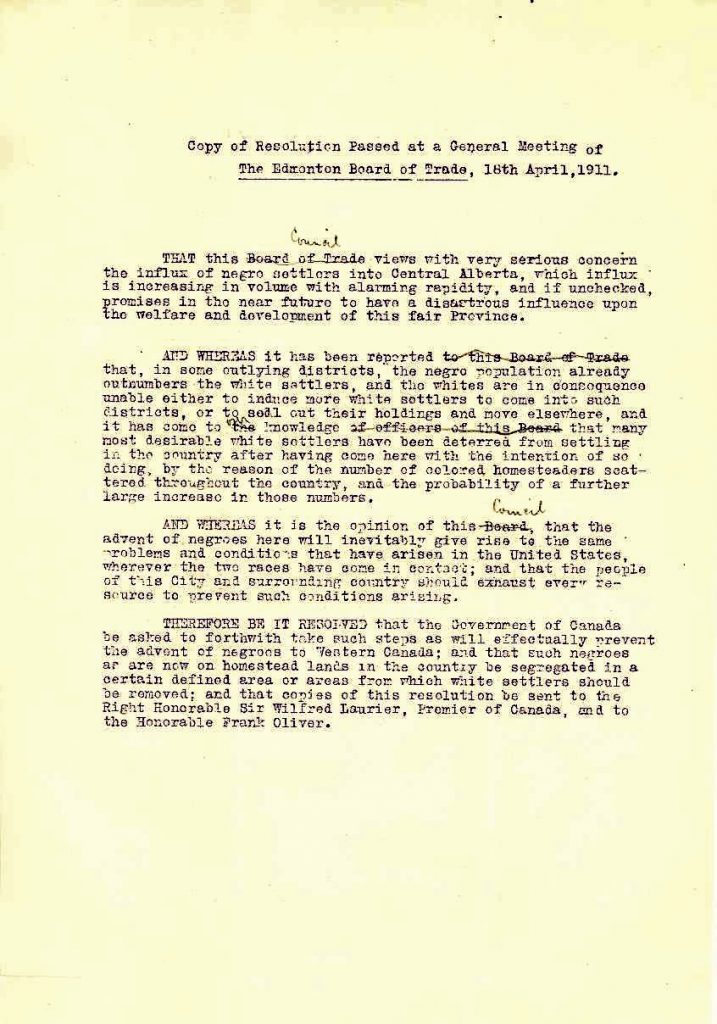

Settlers of African descent who arrived between 1907 and 1912 encountered racist government and private organizational policies.

Resolution of the Edmonton Board of Trade on April 11th, 1911 asking the Government of Canada to restrict the immigration of Black people into Western Canada and to segregate those who were already here. This led to the 1911 Order-In-Council.

Letter courtesy of the City of Edmonton Archives. Click on it for full-sized image.

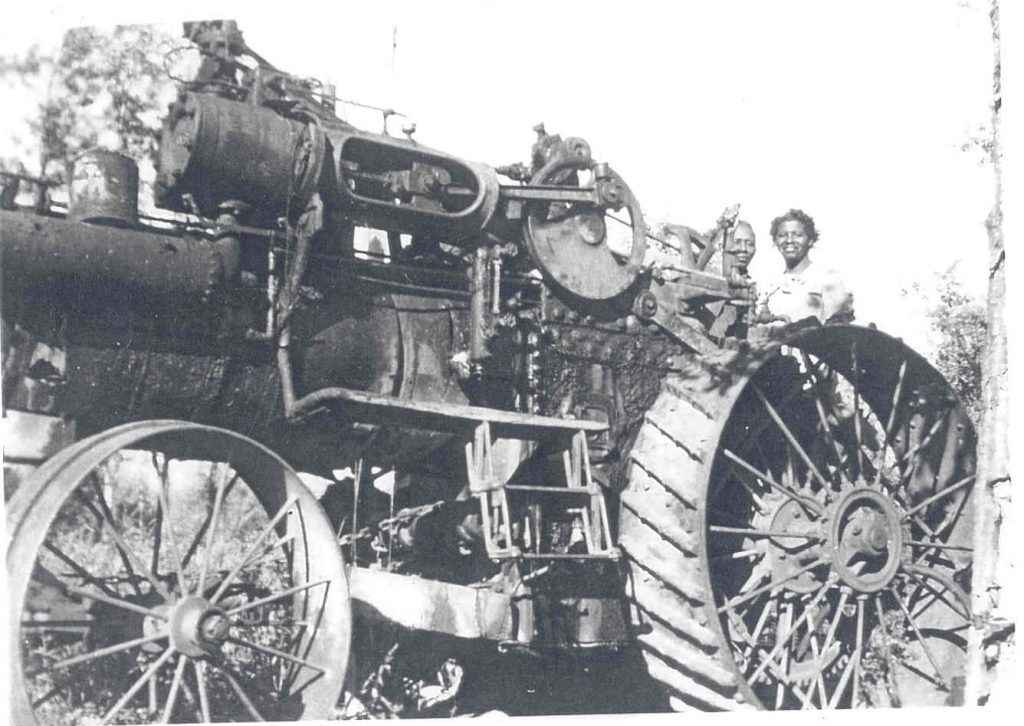

Deemed “unsuitable” future Canadians in a 1911 Order in Council, the Black pioneers established four principal rural farming communities: Pine Creek (Amber Valley); Keystone (Breton); Campsie (near Barrhead); and Junkins (Wildwood). They broke land for farming and built churches and schools.

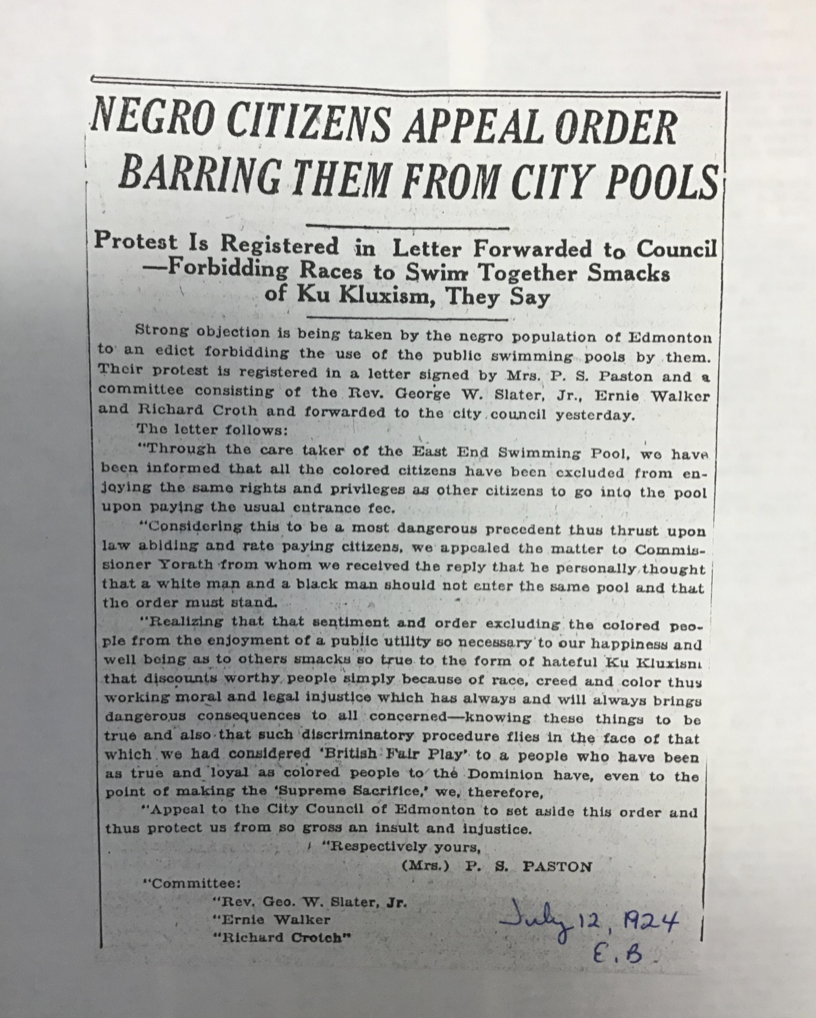

African-Canadians in Edmonton and Calgary interacted with Whites on an ongoing basis, challenging negative stereotypes and discrimination from racists determined to maintain social exclusion and segregation.

Edmonton Bulletin, July 12th, 1924, Image made available through Peel’s Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta Libraries. Click on image for full-sized version.

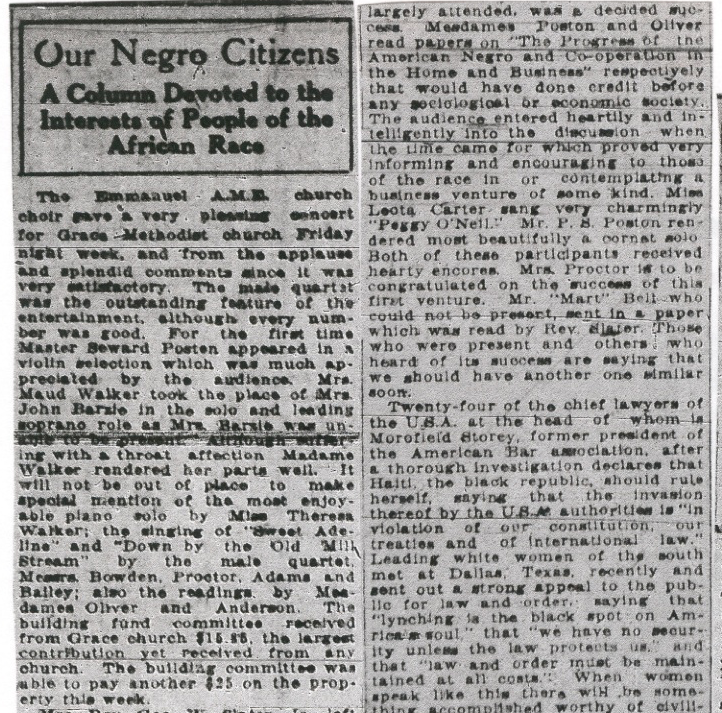

In the 1920s, several social, cultural and political organizations including the Universal Negro Improvement Association, were active in the different communities. Ongoing community columns in the Edmonton Bulletin and Edmonton Journal connected African-Canadians across Alberta.

A column in the Edmonton Bulletin from 1924. Image made available through Peel’s Prairie Provinces, a digital initiative of the University of Alberta Libraries.

During the 1920s and 1930s some community members set up businesses to serve both Blacks and a wider clientele. But most Blacks faced limited employment opportunities. Attempts to increase the provincial Black population through further immigration were stymied.

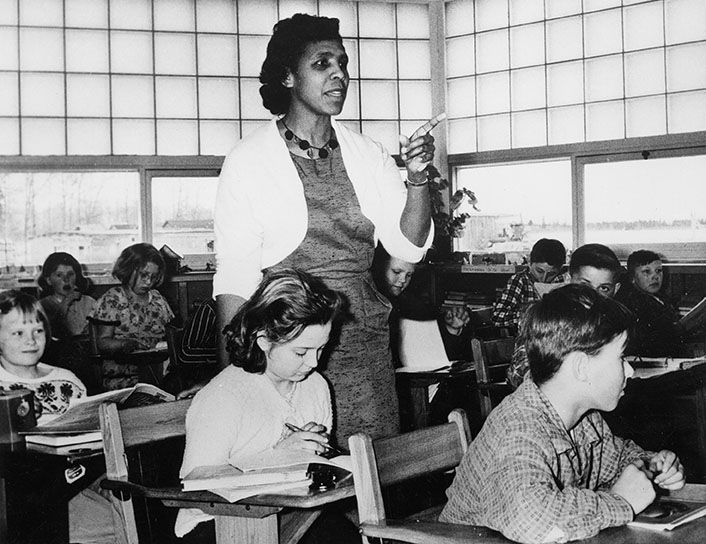

Most women of African descent were directed towards servile roles as domestics, or children’s nurses. A few such as Ruby Lee (Bransford) Edwards and Gwen Hooks persevered to become teachers.

Ruby Lee (Bransford) Edwards, Grassland School, Amber Valley, Alberta, 1959, [NA-704-4], Courtesy of Glenbow Archives, Archives and Special Collections, University of Calgary

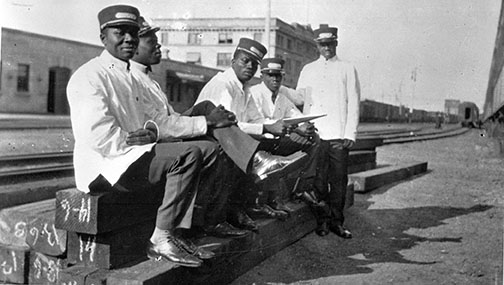

For men, the main job – despite systemic discrimination by white-dominated unions and employers – was “sleeping car porter” on trains. From the mid-1940s, porters in Calgary and Edmonton working for the Canadian Pacific Railway and the Northern Alberta Railway were organized by the US-based International Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, essentially an all-Black union. The union fought for employment, housing, and human rights for all. Calgary Division had an active Ladies Auxiliary. The pioneer communities collectively fought racism through organizations such as the AAACP (Alberta Association for the Advancement of Coloured People) while individuals also pursued legal cases (e.g., Ted King).

A few Caribbean people arrived during the 1950s as preferred professional immigrants, or under the West Indian Domestic Scheme for single women workers that began in 1955. The overall number of Blacks grew from the 1960s onwards with the shift in immigration policies from an overt preference for whites towards a points system. With an increase in Caribbean immigrants, the early pioneer communities, many now living in Edmonton and Calgary, were eclipsed. Many people assumed that every Black Albertan was from “the island.” Caribbean migrants came with skills and training in trades (e.g., oil workers from Trinidad and Tobago, hairdressers) or as professionals (e.g., teachers, veterinarians, stenographers, nurses, and administrators). Many professionals found that their credentials were not fully recognized in Alberta or Canada.

Students and workers from different countries in Africa had always found their way to Alberta, but in the 1990s their numbers began to grow. They included many French-speaking migrants. Some African migrants arrived as refugees from war, or to fill openings in post-secondary education, other professional areas, or the trades. For example, in the southern Alberta city of Brooks, many workers from Sub-Saharan Africa found jobs in the local meatpacking plants. In 2016 Blacks accounted for 14.3% of the population of Brooks. That was well above the national average of 3.5%. Africans are now among the fastest growing groups of new pioneers in Canada. But the continuing racism that they face is exemplified in Edmonton where Statistics Canada reports that the unemployment rate for Black men and women is twice that of the rest of the population.

Photo courtesy of Gord Christie

Interviews with people from Black communities in Alberta

Read We Want to Breathe by Donna Coombs-Montrose

See also: Systemic Racism in Alberta’s History, Temporary Foreign Workers

Further Reading and Viewing on Black Communities in Alberta

24 Days in Brooks, dir. Dana Inskter, prod. Bonnie Thompson. National Film Board of Canada, 2007.

[Peter Jany, an interviewee in this section, and Doug O’Halloran, also interviewed by ALHI, are featured, as is the strike and strike vote at Lakeside Packers)

And Still We Rise: A Black Presence in Alberta, late 1800s – 1970s. Researched and developed by Dr. Jennifer Kelly, Edmonton City as Museum Project Online Exhibition.

Aiello, Rachel, “Canada adds Proud Boys to terror list, bringing range of legal, financial implications,” CTV News, Feb. 3, 2021.

Baergen, W.P., The Ku Klux Klan in Central Alberta. Red Deer, Alberta: Central Alberta Historical Society, 2000.

Black Lives in Alberta: Over a Century of Racial Injustice Continues, Directed by Jenna Bailey, Produced by Deborah Dobbins and David Este, Aspen Foundation of Labour Education, 2021.

Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan. The Black Settlers of Alberta and Saskatchewan Historical Society.

Brown, Edward, “More than 60 years ago a Black teen from Malvern C.I. was told to stop dancing with a white girl on a Buffalo TV show. Toronto exploded,” Toronto Star, Feb. 14, 2021.

Chambers, Allan, Fighting Back: The Calgary Laundry Workers’ Strike of 1995 (Download PDF), Edmonton: ALHI and the Alberta Federation of Labour, 2012.

[Yvette Lynch-Parker was interviewed for this publication – her full interview is here]

Coombs-Montrose, Donna, “My Canada,” Home: Stories Connecting Us All, eds. Tololwa M. Mollel and Scott Sabo. Edmonton, 2017, pp. [Download PDF].

Coombs-Montrose, Donna, “The Porter: Building a Better Canada for All,” Edmonton City as Museum Project ECAMP, Feb. 16, 2021.

Foster, Cecil, They Call Me George: The Untold Story of Black Train Porters and the Birth of Modern Canada. Windsor: Biblioasis, 2019.

Home: Stories Connecting Us All, eds. Tololwa M. Mollel and Scott Sabo. Edmonton, 2017.

John Ware Reclaimed, dir. Cheryl Foggo, prod. Bonnie Thompson and David Christensen. National Film Board of Canada, 2020.

Kelly, Jennifer and Dan Cui, “Racialization and Work,” in Working People in Alberta: A History, ed. Alvin Finkel. Edmonton, AU Press, 2012, pp. 266-286 [Download PDF].

Klaszus, Jeremy, “Cheryl Foggo on Black Life in Alberta,” Sprawlcast, June 6, 2020.

McMaster, Geoff, “Great-granddaughter [Debbie Beaver] of Black settlers chronicles Alberta’s little-known history,” Folio, Feb. 5, 2021.

Miles, Dr. Marianne,” Edmonton Journal Remembering, October 10, 2020

Mohamed, Bashir, Edmonton Anti-Black Racism Toolkit, 2020.

Mohamed, Bashir, “Opinion: Edmonton’s Legacy of Systemic Racism Continues Today,” The Edmonton Journal, June 6, 2020.

Ninth Floor, dir. Mina Shum, prod. Selwyn Jacob, National Film Board of Canada, 2015.

[On the Sir George Williams Computer Incident in Montreal in 1969]

Palmer, Howard and Tamara, “Urban Blacks in Alberta,” Alberta History, v. 29, no. 3 (1981): pp. 8-18.

The Road Taken dir. Selwyn Jacob, National Film Board of Canada, 1996.

[The history of Black sleeping-car porters in Canada]

Schwinghamer, Steve, The Colour Bar at the Canadian Border: Black American Farmers, Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

Secret Alberta: The Former Life of Amber Valley, dir. Neil Grahn, prod. Holly Dupej for TELUS Optik Local, 2016.

Shepherd, R. Bruce, “Diplomatic Racism: Canadian Government and Black Migration from Oklahoma, 1905-1912,” Great Plains Quarterly, 3, no. 1 (Winter 1983), pp. 5-16.

Simons, Paula, “Removing Frank Oliver’s Name Would Whitewash Edmonton’s History,” The Edmonton Journal, August 31, 2017.

Wakefield, Jonny, “After Charlottesville: Police and Activists Look to Counter Alberta’s Extreme Right,” The Edmonton Journal, August 21, 2017.

We Are the Roots: Black Settlers and their Experiences of Discrimination on the Canadian Prairies, Bailey and Soda Films, 2017.